How Stories Enhance, Not Undermine Truth

The Narnia illustrator wept over Aslan before realizing Who he was

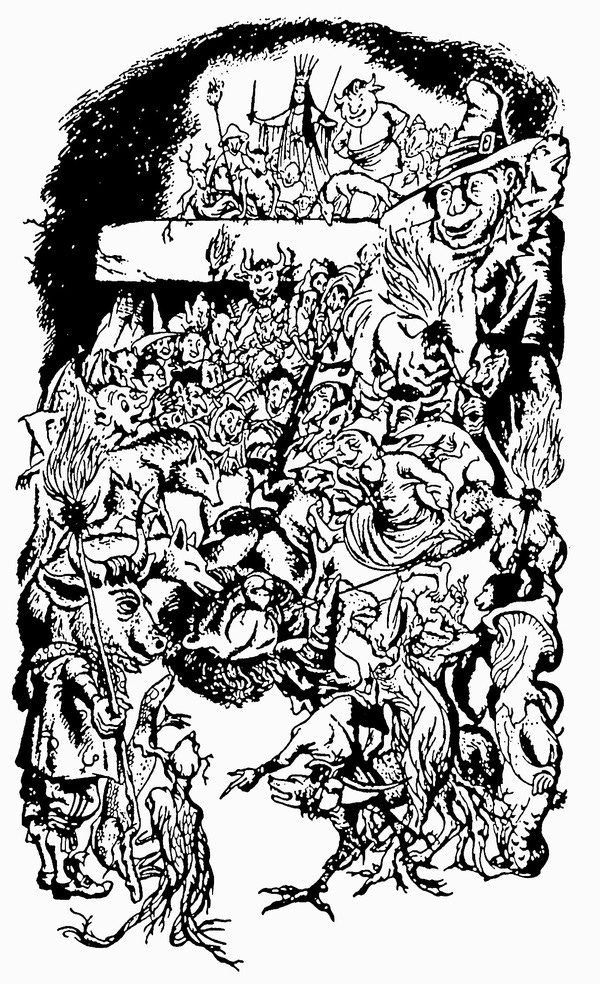

Everyone who has read The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe knows the scene. It’s perhaps the most powerful scene in all of The Chronicles of Narnia.

Aslan slowly makes his way to the stone table to surrender himself to the White Witch. Accompanied part of the way by Susan and Lucy, the great lion takes the last steps on his own and allows himself to be captured.

The assembled ghouls and monsters beat and mock him mercilessly before the witch plunges a knife into him, killing the kingly, innocent lion. Aslan sacrifices himself to free Edmund from the penalty of being a traitor.

When reading through the story, illustrator Pauline Baynes was deeply moved. The awfulness of what the White Witch and her evil henchmen were doing to Aslan weighed on her. The story had broken her heart and left her struggling to depict such a tragedy.1

But she finished that drawing and the rest of the book’s illustrations. It was only much later that she realized the true depth of Aslan’s sacrifice and his story. She told Walter Hooper that it was only much later when she realized “Who he was meant to be.”2

She wasn’t really weeping for the lion of Narnia. In actuality, she was weeping for the Lion of Judah. Without recognizing it, the story of Aslan connected her to the story of Christ. This was exactly what Lewis was trying to do.

In explaining why he wrote the Narnia stories, Lewis said he had both teaching and artistic reasons for his work. He thought fairy tale stories would be the best way to communicate spiritual truth effectively and remain true to the artistic images that had popped into his mind.

In his essay “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s to Be Said” (from On Stories: And Other Essays on Literature), Lewis wrote:

I thought I saw how stories of this kind could steal past a certain inhibition which paralyzed much of my own religion in childhood. Why did one find it so hard to feel as one was told one ought to feel about God or about the sufferings of Christ? I thought the chief reason was that one was told one ought to. An obligation to feel can freeze feelings. And reverence itself did harm. The whole subject was associated with lowered voices; almost as if it were something medical. But supposing that by casting all these things into an imaginary world, stripping them of their stained-glass and Sunday school associations, one could make them for the first time appear in their real potency? Could one not thus steal past those watchful dragons? I thought one could.

Baynes’ account shows just how perfectly Lewis had achieved his goal. With the story of Aslan, Lewis delivered deep truths of the gospel by stripping away much of the stained-glass trappings accumulated over the years and placing the core elements in a compelling story.

The church must continually relearn this lesson. Truth is often best presented in the form of a story. God recognized this. He gave us a book centered around one story—the rightful King doing whatever it takes to win His people and reclaim His throne. That doesn’t take away from the rational truth claims made in Scripture; it enhances them.

Think how Jesus used parables to make piercing points. He wasn’t ignoring God’s truth. He didn’t use stories because He was embarrassed by the truth. Jesus communicated in a way that helped His readers better understand the truth.

In a culture often driven more by emotion than logic, Christians must be prepared to do what C.S. Lewis and Jesus did—marshal attacks on both fronts.

Don’t jettison rational arguments. Be prepared to defend the Christian faith based on reason. But we should also work to weave Christianity into the hearts of people through stories.

Almost as much as her illustrations, the tears of Pauline Baynes show just how effective Lewis was at delivering truth through the vehicle of story.

Too often, when we see cultural dragons in someone’s life, we think we should charge in with every argument in our arsenal. Or worse, we assume the only solution is to attack the individual.

Frequently, the dragon resists them all and becomes only entrenched. Instead, sometimes, we need lions not to attack, but to sneak.

Sources:

Past Watchful Dragons: The Origin, Interpretation, and Appreciation of the Chronicles of Narnia — Walter Hooper

On Stories and Other Essays on Literature — C.S. Lewis

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe — C.S. Lewis

For more on the Narnia stories, don’t miss our new read-along of The Magician’s Nephew. The first chapter-by-chapter breakdown for paid subscribers starts Friday.

More from The Wardrobe Door

Archive

Recent

Elsewhere

Fewer Than 1 in 3 Churchgoers Read the Bible Daily — Lifeway Research

Some have said that Baynes continually wept on her paper and had to keep restarting the illustration. While it sounds plausible, I was unable to find a source. In Past Watchful Dragons, Walter Hooper does say that Baynes told him that “she was deeply moved by the sacrifice of Aslan.”

Baynes told someone else that she realized Aslan was a supposal for Jesus “long afterwards. At the time, I just thought they were marvelous stories.”

Aaron, if you don't know Martin Shaw, you should really look him up here and on YouTube. He's all about myths and stories connecting us to the divine. And he only recently realized they were connecting him to Jesus and joined the church.