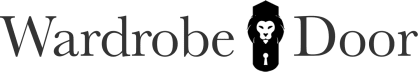

“The Magician’s Nephew” Introduction

C.S. Lewis Read-Along, Vol. 6, Issue 1

Welcome to our spring C.S. Lewis read-along. For the next few months, we’ll be going chapter-by-chapter through The Magician’s Nephew. This introduction is open to everyone. The upcoming full chapter discussions will only be available for paid subscribers.

The Magician’s Nephew describes the beginnings of Narnia and how our world became connected to it, so let’s explore those connections together. What works, events, and people contributed to the book? What was C.S. Lewis trying to “sneak past the watchful dragons” of the reader? What can we draw from the books for our own lives?

The Magician’s Nephew fast facts

Published in the U.K. on May 2, 1955 (Oct. 4 in the U.S.) as the sixth Narnia book

Written on and off again from 1949 to 1954

The last Narnia book finished

The first book chronologically

The events take place in 1900 our time and describe the creation of Narnia

Dedicated to the Kilmer family, friends of Mary Willis Shelburne (the “American lady” of Letters to an American Lady)1

Set to be adapted into a film by Greta Gerwig later this year

Background for The Magician’s Nephew

For all of Lewis’ skill as a writer, he often struggled when the subject became too close. Most of his works maintain a personable, but not personal, air. Even with his autobiography, Surprised by Joy, some of his friends dubbed it “Suppressed by Jack.” His most personal book, A Grief Observed, he wrote under a pseudonym.

This difficulty is likely why it took him years to complete The Magician’s Nephew. It feels the most personal of the Narnia books, with a small boy struggling with a dying mother. Lewis lost his own mother the year he turned 10, even younger than Digory in the story. Both Lewis and Digory also grew up to be professors who had life-changing experiences hosting evacuee children during World War II.

Once Lewis finished writing The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, most remaining Narnia books were written within months of starting them—except The Magician’s Nephew. He began trying to tell the story of Narnia’s creation immediately after finishing Wardrobe. A friend had asked him how the lamp post came to be in the woods, so he set about answering that question.

He read two chapters of this attempt to Roger Lancelyn Green in June 1949. Because Lewis threw away much of his papers, however, we only have a few pieces of the Narnia stories that aren’t the final versions. The largest is called the “Lefay fragment,” which was Lewis’ first version of what would become The Magician’s Nephew story.2

In the text we have, republished in Walter Hooper’s Past Watchful Dragons, a young Digory lost both his parents and is staying with his Aunt Gertrude. He can talk to animals and trees.3 However, he loses this ability when Polly, the young girl next door, convinces him to cut off a limb from an oak tree to make a raft. The next day, Digory’s godmother, Mrs. Lefay, appears and tells him he looks “exactly like what Adam must have looked five minutes after he’d been turned out of the Garden of Eden.”

Pieces of the fragment were pulled into other Narnia stories: Gertrude is described much like the female head of Experiment House in The Silver Chair, and a squirrel is named Pattertwig, like in Prince Caspian. But the bulk of what is reused shows up in The Magician’s Nephew, with characters named Digory, Polly, and Lefay, who would move from Digory’s to Uncle Andrew’s godmother.

Lewis first attempted to write the creation of Narnia in 1949 in a piece of a story that has been called the Lefay Fragment.

Both Green and Hooper also believe this fragment was Lewis trying to tell the Narnia creation story, but he abandoned it later in 1949. Instead, he began Prince Caspian and finished it that year. The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, The Horse and His Boy, and The Silver Chair quickly followed in that order from late 1949 through early 1951.

Lewis returned to The Magician’s Nephew in 1951. By that fall, Green says the book was around three-fourths finished, but wasn’t polished. Green complained about a section where Digory visits Charn multiple times and stays in a farm cottage with an old countryman named Piers and his wife. He said it seemed “quite out of harmony with the rest of the book.” Once again, Lewis paused his work on the story.

In the meantime, he completed the significant academic work, English Literature in the Sixteenth Century. When that was finished, he returned to Narnia, but with The Last Battle. Once the end of Narnia was complete, Lewis finally felt able to finish the beginning.

In March 1953, Lewis told his publishers that the last Narnia story was finished. The next February, Green read the finished manuscript and called it “the best of the lot,” but noted it was “vastly improved by the omission of the long section about Piers the Plowman—which I take some credit for persuading Jack to cut out.”

On the pages of The Magician’s Nephew

In a 1961 letter to a young girl, he explained that the “whole Narnian story is about Christ,” but he pushed back on an allegorical interpretation.4

Rather, the stories are supposals, answers to the question: “Supposing there really were a world like Narnia, and supposing it had (like our world) gone wrong, and supposing Christ wanted to go into that world and save it (as He did ours) what might have happened?” About The Magician’s Nephew, Lewis said it “tells the creation and how evil entered Narnia.”

Obviously, the story pulls from the biblical creation story in Genesis, which Lewis also used in Perelandra. The landscape and animals are created. Humans are given dominion over creation. A garden contains a tree with the fruit of life. A woman takes the fruit, eats it, and offers it to someone else. There are also aspects of John Milton’s poetic retelling of the creation story, Paradise Lost. But, as with all of Lewis’ writing, he draws from a multitude of sources to create something unique.

Algernon Blackwood’s Education of Uncle Paul (1909) features children exploring the land beyond the crack between yesterday and tomorrow, which allows people to find lost things and changes perspectives from cynical to imaginative. It has the same feeling as the Wood Between the Worlds in The Magician’s Nephew.

In 1916, Lewis wrote to Arthur Greeves to say he had “never read anything like [Blackwood’s story]. … When you have got it out of your library and read how Nixie and Uncle Paul get into a dream together and went to a primaeval forest at dawn to ‘see the wind awake’ and how they went to the ‘Crack between yesterday and tomorrow’ you will agree with me.”

In his letters with Greeves, Lewis also frequently mentions William Morris, a late 19th-century English writer influential in the establishment of fantasy. One of his works, The Wood Beyond the World (1894), likely served as naming inspiration for “The Wood Between the Worlds” in The Magician’s Nephew. Additionally, an iron ring symbolizes the enslavement that keeps a character in the wood.

Another literary source is one of Lewis’ favorite childhood (and adulthood) authors: Rider Haggard. We talked about She: A History of Adventure before, as the character She (aka Ayesha) helped inspire the White Witch, so obviously, the character is relevant as we discuss Jadis’ origins.

The story features a hall of petrified statues containing the great leaders of the tribe. The heroes encounter She in a ruined city in Africa described as a “charnel house.” In the sequel Ayesha: The Return of She, there’s a great battle between She, an immortal queen, and her rival, an ancient princess. You can see some of the bits that would become Jadis battling her sister over Charn.

Lewis also drew from his real life, beyond his mother’s sickness. His brother, Warren Lewis, described Robert Capron, the headmaster at a school both Lewis boys attended, like how The Magician’s Nephew describes Uncle Andrew.5

All these literary and personal experiences, both enjoyable and terrible, came together into the beautiful story of The Magician’s Nephew. In many ways, that’s the story itself. Digory and Polly struggle through pain and hardship, brought about by others and self-inflicted, but in the end, Aslan uses it all for good.

In Lewis scholar Michael Ward’s Planet Narnia, he says this book connects to Venus, the morning star and goddess of love. In The Narnia Code, Ward writes, “Digory is forced to choose between his love for Aslan and his love for his mother.” The boy chooses Aslan, resting in the goodness of the Lion. We often face a similar choice to trust in God.

Reading The Magician’s Nephew, we’re reminded that God is lovingly crafting our story from the beginning to the end. Even the difficult moments are no match for His storytelling prowess. We may not see our heartbreak immediately reversed as Digory saw with the healing of his mother—Lewis didn’t—but we know that our current circumstances are only part of the story God is writing, and His story is not over until He says so.

In the meantime, even as we may feel like our life resembles the ruined city of Charn, we trust that God is “working all things together for the good of those who love and are called according to His purposes.”

Next time: Chapter 1, “The Wrong Door”

Further up and further in

Resources used:

Books by C.S. Lewis

The Magician’s Nephew — C.S. Lewis

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe — C.S. Lewis

Prince Caspian — C.S. Lewis

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader — C.S. Lewis

The Silver Chair — C.S. Lewis

The Horse and His Boy — C.S. Lewis

The Last Battle — C.S. Lewis

Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life — C.S. Lewis

The Ransom (or Space) Trilogy — C.S. Lewis

A Grief Observed — C.S. Lewis

Letters to an American Lady — C.S. Lewis

The Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis, Volume 1: Family Letters, 1905-1931 — Editor: Walter Hooper

The Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis, Volume 2: Books, Broadcasts, and the War, 1931-1949 — Editor: Walter Hooper

The Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis, Volume 3: Narnia, Cambridge, and Joy, 1950-1963 — Editor: Walter Hooper

Books about C.S. Lewis

C.S. Lewis: The Companion and Guide — Walter Hooper

Past Watchful Dragons: The Origin, Interpretation, and Appreciation of the Chronicles of Narnia — Walter Hooper

Companion to Narnia: A Complete Guide to the Magical World of C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia — Paul Ford

Into the Wardrobe: C.S. Lewis and the Narnia Chronicles — David C. Downing

Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C.S. Lewis — Michael Ward

The Narnia Code: C.S. Lewis and the Secret of the Seven Heavens — Michael Ward

The C.S. Lewis Readers’ Encyclopedia — Editors: Jeffrey Schultz, John G. West, Jr.

Becoming C.S. Lewis: A Biography of Young Jack Lewis — Harry Lee Poe

The Making of C.S. Lewis: From Atheist to Apologist (1918-1945) — Harry Lee Poe

The Completion of C.S. Lewis: From War to Joy (1945-1963) — Harry Lee Poe

C.S. Lewis: A Life — Alister McGrath

The Narnian: The Life and Imagination of C.S. Lewis — Alan Jacobs

C.S. Lewis: A Biography — Roger Lancelyn Green, Walter Hooper

Works by others

Paradise Lost — John Milton

Education of Uncle Paul — Algernon Blackwood

The Wood Beyond the World — William Morris

She: A History of Adventure — Rider Haggard

Ayesha: The Return of She — Rider Haggard

The Sword in the Stone — T.H. White

Mistress Masham’s Repose — T.H. White

Podcasts:

Wade Center Podcast “Into Narnia, Vol. 6, The Magician’s Nephew” — Marion E. Wade Center, Wheaton College

The C.S. Lewis Podcast with Alister McGrath “#23 The Magician’s Nephew” — Premiere Insights

Previous articles in the C.S. Lewis read-along

To catch-up with our previous read-alongs, you can check out the conclusions to each book for links to all the chapter-by-chapter discussions.

In a February 1954 letter to Shelburne, Lewis said the dedication of “the next story” was still vacant and asked if the family would like to have it dedicated to them. In a March letter to the Kilmers, he says that “your book went off to the publisher last week.” In a July 1955 letter, he tells them he is happy they enjoyed the book. He wrote, “It would have been awkward if the one dedicated to you had turned out to be just the one of the whole series that you couldn’t stand!”

Walter Hooper says we only have this 26-page handwritten fragment because it was in a notebook with English literature notes that Lewis wanted to preserve. Most often, Lewis discarded and destroyed manuscripts and notebooks.

It may be that Lewis was inspired by T.H. White’s 1938 novel, The Sword in the Stone, in which a young Arthur, unaware that he is heir to the throne, is tutored by Merlin and learns to communicate with animals. Lewis had read the book but said it was spoiled by “vulgarity.” He preferred White’s latter work, Mistress Masham’s Repose. In 1947, Lewis wrote to White to tell him how much he enjoyed that book and invited him an Inklings meeting if he were ever in Oxford.

In a 1960 letter to another young girl, he explained that the Narnia creation story is “the son of God creating a world (not specifically our world).”

Capron was a cruel schoolmaster who was eventually forced out of education and died in an asylum. The terror inflicted on students and others at Wynyard is why Lewis, in Surprised by Joy, calls it Belsen, the name of a Nazi concentration camp.

Woohoo! We're starting another Narnia book! I always enjoy these read-throughs immensely. Thanks, Aaron!