Why read “The Chronicles of Narnia”?

Narnia Read-Along: Introduction 1

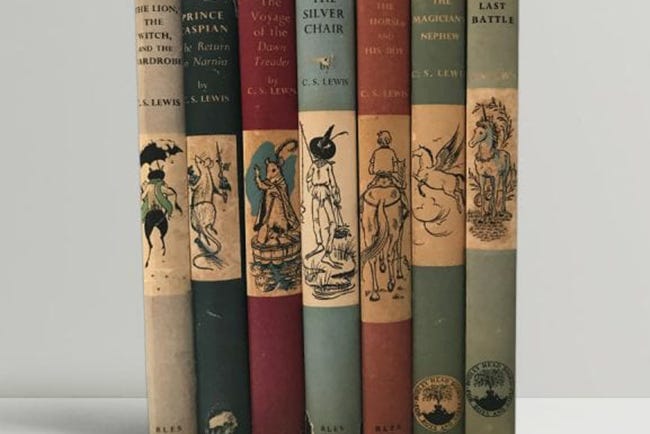

In one sense, asking why one would read “The Chronicles of Narnia” seems an absurd question. It’s a beloved and award-winning series with millions of copies sold and translated into close to 50 languages. The books have been adapted for radio, stage, TV, and film, while inspiring many of the most successful modern fantasy writers like Neil Gaiman and J.K. Rowling.

Yet, how many children’s book series written by a childless bachelor remain popular 70 years after their publication? Friends and family laughed when Lewis broached the idea of writing for children. Lewis didn’t think his work would last after his death. J.R.R. Tolkien, friend of Lewis and creator of his own famous fictional world, disliked the Narnia books. “The Chronicles of Narnia” have been criticized as disjointed and sloppy, dismissed as too preachy and pedagogical, castigated as racist and sexist.

But here we are, still reading and enjoying them today. So why do the books remain beloved best-sellers? Let me borrow a habit from Lewis and coin a phrase. The books endure because of their imaginative simplexity.

First, the books awaken the best parts of our imagination. Lewis’ evocative language and clear writing allow us to bridge the gap that exist between not only our world and the fictional Narnia, but our present day and mid-20th century England. We can picture ourselves playing hide-and-seek in Professor Kirke’s labyrinthine house and feel the cold blast of snowy air as Mr. Tumnus walks toward the lamp post in the woods.

But even as they allow us to mentally explore those worlds, the books re-enchant our own disenchanted world. In The Weight of Glory, Lewis says that “you and I have need of the strongest spell that can be found to wake us from the evil enchantment of worldliness.” He contends literature can serve as a good spell to counteract the spell of the world that prevents us from seeing all that is around us.

Who hasn’t hoped they could walk through a rack of clothes and discover an adventure on the other side? More than picturing ourselves going into a new world, however, the books allow us to see the adventure present in our everyday. Forests seem more exciting and home to the extraordinary. Even exploring indoors, the nooks and crannies carry mysterious possibilities. As Lewis wrote in “On Three Ways of Writing for Children,” the one who reads fantasy “does not despise real woods because he has read of enchanted woods: the reading makes all real woods a little enchanted.”1

Through the Narnia series, Lewis gives us the gift of imagining what another world would be like, but also the joy of seeing the magic in our own world.

Secondly, the Narnian series have a “simplexity.” The books are simple enough a child can grasp them, but contain enough complexity to reward numerous adult readings. Young children can breeze through the stories enjoying the colorful characters and vibrant scenes. Adults, or at least adults with childlike sensibilities, can appreciate the depth of emotions involved in pivotal scenes and the complicated relationships between characters.

I’ve read the books since I was a child. I’ve read them to my children. I’ve read them individually as an adult. I’ve read them as part of a book study. In all the times I’ve read them, I’ve never read them without finding something new that moves me. We continue to reread them because we know the experience will be worth it. Well-worn paths most often have the greatest views.

Narnia endures because Lewis gives us a story that captures our heart and refuses to let go. Narnia endures because it reflects the grand narrative, the gospel.

The series immerses the reader in the story of Jesus, not through a religious retelling but an imaginative supposal. While many have accused him of writing a Christian allegory, Lewis rejected that label. He referred to Narnia as a “supposal.” Aslan isn’t exactly an allegorical expression of Jesus. He’s an imaginary answer to the question: “What might Christ become like if there really were a world like Narnia and He chose to be incarnate and die and rise again in that world as he actually has done in ours?”2

Before he wrote “The Chronicles of Narnia,” Lewis had already written most of his apologetic books and delivered the BBC radio addresses that would become Mere Christianity. He had spent time speaking to both religious and secular audiences about the claims of Christianity. His move into children’s literature was not a retreat from his work as an apologist but a redeployment to a different front. In fact, in a letter to Carl F.H. Henry rejecting an offer to write “direct theological pieces” for the newly formed Christianity Today, Lewis says he’s moving beyond the “frontal attacks” of his previous works.

In his essay, “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s to Be Said,” Lewis writes that he never set out to write Christian truths taught through a meager story. He did believe, however, that fairy stories told from a Christian perspective could help people overcome their objections to the faith. “But supposing that by casting all these things into an imaginary world, stripping them of their stained-glass and Sunday school associations, one could make them for the first time appear in their real potency? Could one not thus steal past those watchful dragons?”3

That’s why we read “The Chronicles of Narnia.” We still have “watchful dragons” that want to keep us from the beauty of the gospel. In order to sneak past them, we can turn and return to the imaginative simplexity of C.S. Lewis’ fictional world. I’m looking forward to reading them again with you.

Next week, before we start reading “The Chronicles of Narnia,” we have to discuss exactly where we should start. Should we begin with the traditional publication order, beginning with The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, or should we start with the new chronological order used by publisher HarperCollins, beginning with The Magician’s Nephew? Perhaps unsurprisingly, I have strong feelings on the subject.

“On Three Ways of Writing for Children” contained in On Stories and Other Essays on Literature

The Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis, Vol. 3. December 29, 1958 letter to Mrs. Hook.

“Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s to Be Said,” contained in Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories