The Horse and His Boy: Chapter 10 “The Hermit of the Southern March”

C.S. Lewis Read-Along, Vol. 5, Issue 11

Shasta finds the issue with sanctification. Tasks only grow more difficult. Bree is humbled, but he has to learn the best way to respond.

Shasta’s heart fainted at these words for he felt he had no strength left. And he writhed inside at what seemed the cruelty and unfairness of the demand. He had not yet learned that if you do one good deed your reward usually is to be set to do another and harder and better one. But all he said out loud was: “Where is the King?”

Chapter 10 “The Hermit of the Southern March”

As the story moves away from the desert of Tashbaan and into the mountains of Archenland, Lewis gives us new splashes of color—the “green North” and “blue peaks.” The hills look “greener and fresher than anything that Aravis and Shasta, with their southern-bred eyes, had ever imagined.”

Proud Bree seems content to celebrate their achievements as they crossed Winding Arrow River and officially entered Archenland. Practical Hwin worries if they made it in time.

Sounding like J.R.R. Tolkien and one who frequently walked the hills of Ireland and England, Lewis gives us a list of trees the group encounters: “oaks, beeches, silver birches, rowans, and sweet chestnuts.”1 The four also see rabbits and deer. Aravis, whose heart is almost ready to be a Northerner, calls it all “simply glorious.”

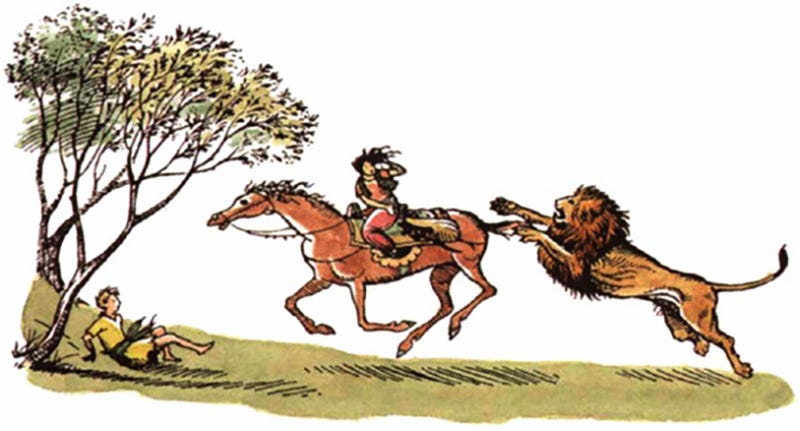

But then, Hwin’s worst fears are realized. They spot Rabadash’s army blazing across the desert and reaching the river. The horses and humans make a dash for Anvard. But the horses weren’t doing all they could; they were doing “all they thought they could; which is not the same.” That was about to change.

They expected to hear the sounds of a Calormene army, but instead, it’s the roar of a lion. Suddenly, Bree was finally truly moving as fast as he could. He and Shasta sprinted past Hwin and Aravis.

Ahead, they see a wall with a bearded man wearing a “robe colored like autumn leaves” standing in an open gate, but behind them, the lion was closing in on Hwin. Shasta jumped off Bree and ran back toward the danger. At that moment, the lion was on its hind legs with claws out, tearing into Aravis’ back.

But as Shasta confronts the snarling lion, he realizes he has nothing, not even a stick. He does all he can do—shout at the lion: “Go home! Go home!” For some reason, the lion stops immediately and runs in the opposite direction.

Hwin and Aravis basically collapse through the gate, where the man welcomes them. Shasta asks if he was King Lune, but the man says he is the Hermit of the Southern March. “If you run now, without a moment’s rest,” he tells Shasta, “you will still be in time to warn King Lune.”

Lewis says Shasta “writhed inside at what seemed the cruelty and unfairness of the demand” because he “had not yet learned that if you do one good deed, your reward is usually to be set to do another and harder and better one.” This is another aspect of sanctification.

The Narnia books often depict portions of the outcome of sanctification. Edmund and Eustace become different boys in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. Jill grows to accept responsibility in The Silver Chair. Digory learns from his mistakes in The Magician’s Nephew. Here, Aravis learns to be a Narnian.

But with Shasta, we see the seemingly unpleasant side of maturation and growing in Christlikeness. For that to happen, we have to be pushed further than we’ve gone before. That always comes from obedience, even (especially) when we don’t feel like it.

“Obedience is the key to all doors: feelings come (or don’t come) and go as God pleases,” he wrote in a 1950 letter. “We can’t produce them at will and mustn’t try.”