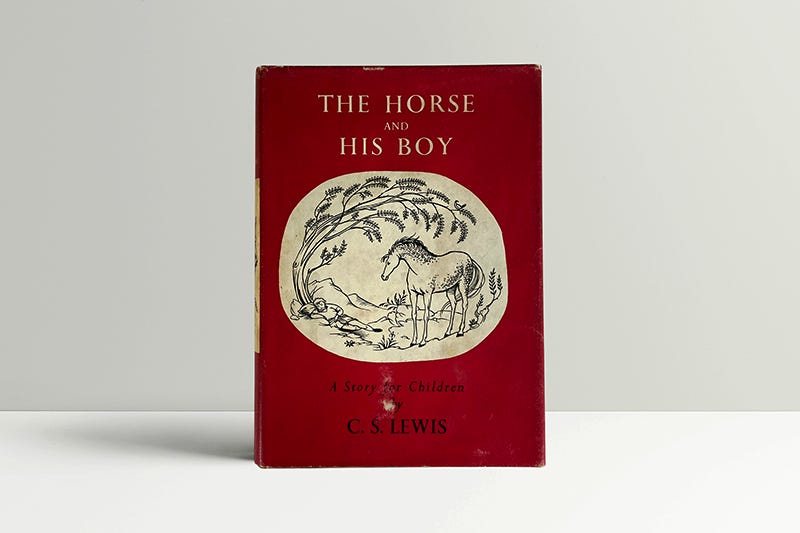

“The Horse and His Boy” Introduction

C.S. Lewis Read-Along, Vol. 5, Issue 1

The Horse and His Boy follows an adventure into Narnia, so why don’t we join them? What works, events, and people contributed to the book? What was C.S. Lewis trying to “sneak past the watchful dragons” of the reader? What can we draw from the books for our own lives?

Welcome to our fall C.S. Lewis read-along. For the next few months, we’ll be going chapter-by-chapter through The Horse and His Boy. This introduction is open to everyone. The upcoming full chapter discussions will only be available for paid subscribers.

Get to know C.S. Lewis better and read his works more deeply. An annual subscription will take you through this read-along and the following one this Spring. Go through The Wardrobe Door as a paid subscriber with this limited-time offer.

The Horse and His Boy fast facts:

Published on Sept. 6, 1954, as the fifth Narnia book

Written between the spring and summer of 1950

The fourth Narnia book finished

Chronologically, the third Narnia book (sort of)1

The events take place in 1014 Narnian time, one year before the Pevensies return to England in 1015. In our time, their entire reign, including this story, happened in 1940.

Dedicated to David and Douglas Gresham, his eventual stepsons

The last book Lewis published with Geoffrey Bles, the original Narnia publisher2

The last Narnia book written before The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was published in October 1950

Background for The Horse and His Boy

Many of us have been inspired by reading C.S. Lewis’ work, but seemingly so was C.S. Lewis. He wrote The Horse and His Boy over three months or so during late spring and early summer in 1950, after re-engaging with a couple of his books.

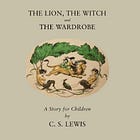

As he was working through the proofs of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe to be published later in the fall of 1950, he realized he’d never explored much of the Golden Age of Narnia, the 15 years when the Pevensies ruled in Narnia before returning to our world.

As such, this is the only book in the series that does not feature any character entering Narnia from our world. All the other books start in our world and follow someone into Narnia. The Horse and His Boy begins in Narnia, or at least Calormen.

This is why the book is considered no. 3, according to the new chronological ordering, after The Magician’s Nephew and The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. But that’s not entirely accurate. The whole of The Horse and His Boy takes place during The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, as it happens before they stumble through the wardrobe and back into our world.3

Additionally, during the season Lewis was composing The Horse and His Boy, he was reading The Problem of Pain because the book was being translated into French. He wrote a specific foreword for it and an additional footnote. Lewis also references The Problem of Pain repeatedly during letters at this time. You can see how The Horse and His Boy wrestles with suffering and meaning.

While Lewis was writing Narnia, he was also researching and composing his spiritual autobiography Surprised by Joy. This enabled him to reconnect with childhood memories, both good and bad, that he drew upon for all of the Narnia stories, including The Horse and His Boy.

Happenings in his life at the time also influenced the book. Mrs. Moore moved to a nursing facility in April 1950 because Lewis was no longer able to care for her at home. His brother was in and out of rehabilitation centers for alcoholism. Lewis wasn’t just writing about suffering; he was experiencing it. In a July 1950 letter, he wrote, “I am working at high pressure.”

Outside of his family, his friendship circle was also in a time of transition. In October 1949, he had read the final text of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, the work Lewis had long encouraged and championed. Yet, the Inklings had ceased to meet as a literary group around the same time.

In March 1949, Lewis met with a former student, Roger Lancelyn Green, who was more supportive of Narnia than Tolkien had been. Like Lewis had done for Tolkien and Middle-earth, Green encouraged Lewis in his fantasy endeavors. Green even suggested the title “The Chronicles of Narnia” for the entire series.

Also, Joy Davidman Gresham first wrote to him in January 1950, a few months before he began The Horse and His Boy. Two years later, she came to England and met Lewis in person. She returned to the United States in January 1953 but flew back to England in November with her two sons after divorcing her husband for having an affair with her cousin. Lewis had received proofs for The Horse and His Boy in September 1953. It was published in 1954 and dedicated to Gresham’s sons, David and Douglas—the first dedication to someone other than the children of fellow Inklings.

In December 1954, Lewis wrote in a letter, “The Horse gets good reviews in USA, but few, and chilly, in England.” I’m not sure if Lewis was correct about the “chilly” response. He tended to downplay the popularity of his work. As you’ll see, The Horse and His Boy has some of the most poignant scenes in all of Narnia.

In the pages of The Horse and His Boy

As was often the case, Lewis needed help naming The Horse and His Boy. He was still trying to establish the name in April 1953. He had to quickly settle on a title because it would be in The Silver Chair, published that September. Lewis wrote to his publisher, Geoffrey Bles, and asked for reactions to these suggestions: “The Horse and the Boy (which might allure the ‘pony-book’ public) – The Desert Road to Narnia – Cor of Archenland – The Horse Stole the Boy – Over the Border – The Horse Bree.”

In this same letter, Lewis spoke to Bles about how he’d like Pauline Baynes to illustrate the book. It’s here that we can discuss one of the more common misunderstandings about The Horse and His Boy.

People often believe the book presents negative stereotypes of Arabic or Muslim people, but the story does not draw on any actual Middle Eastern nations or cultures. Lewis had never been there. He didn’t speak much about the region or the religion. When he did mention Islam or Muslims in his writings, it was often just part of distinguishing Christianity from other world religions.

For The Horse and His Boy, he drew specifically from the folktales contained in A Thousand and One Nights. Lewis had read it earlier and returned to it when an Arabic student of his began studying it. It’s worth noting that Lewis likely got the name “Aslan” from the English translation of the book. In one story, Aslan is a young boy trying to clear his father’s name. A footnote says “aslan” means lion.

In A Thousand and One Nights, you find horses chased by lions, shape-shifting supernatural beings, and a crowded city with tombs outside—all components that Lewis weaved into the story of The Horse and His Boy.

Lewis constructing a culture based on these stories would be like a non-European creating a fictional culture based on the Grimm’s Fairy Tales. It might appear vaguely European, but unaware readers may assume Europe had significant problems with evil step-mothers and wolves dressing up as grandmothers. You’d be hard-pressed to argue the non-European crafting that fictional culture was being hateful toward real Europeans.

Additionally, while Lewis drew from those Arabic folktales, he also deviated extensively from Islamic culture. Calormen is a polytheistic culture, worshipping deities including Tash, Azaroth and Zardeenah. Also, they make physical idols of Tash. Both of those are completely contradictory to Islam.

Lewis’ letter to Bles about Baynes’ illustrations also makes clear, he had something different in mind than a lampooning of Arabic cultures. He says she should base her pictures on A Thousand and One Nights or “on her picture of Babylon and Persepolis (all the Herodotus and Old Testament orient) or any mixture of the two.”4

In a January 1954 letter to Baynes herself, Lewis felt she captured the essence of the story. He praised several illustrations, particularly her drawing of Tashbaan. “We [he and Bles] only got the full wealth by using a magnifying glass! The result is exactly right,” he wrote.

In this book, Lewis wanted to make a land, people, and culture that felt at home in the desert. The name Calormen comes from the Latin word for heat, calor, which is where we get the English word “calorie.”

As with everything else he wrote, Lewis was drawing from numerous literary wells, not only A Thousand and One Nights. Shakespeare, the father of twins himself, incorporated twins separated at birth into The Comedy of Errors and twins separated at sea in Twelfth Night. In The Prince and the Pauper, Mark Twain has a poor boy swap places with the crown prince because they look so similar.

In Greek mythology, Castor and Pollux are twins. Homer mentions them in The Iliad and The Odyssey. Homer describes Castor as a breaker of horses. You can see elements of Cor and Shasta, the two names of the eponymous “boy,” in the name Castor. His brother Pollux is a great boxer. Likewise, Corin constantly wants to box and fight in the story. Eventually, he earns the name “Thunderfists” after boxing a bear.

In Planet Narnia, Michael Ward connects The Horse and His Boy with Mercury, the messenger god, and the name of the metal also known as “quicksilver.” The planet Mercury also rules the twin constellation Gemini. As he’s the god of language, the book focuses on describing the different languages of the Calormene and Narnians. Aslan is also called “the Voice.”

As for Lewis himself, he explained the meanings behind all of his Narnia books to Anne Jenkins in a 1961 letter. He said The Horse and His Boy was about “the calling and conversion of a heathen.” Yes, we will read the conversion journey for Shasta, but again, Lewis is downplaying or at least simplifying all that is contained in this story.

The Horse and His Boy is a masterful and powerful depiction of God’s providence. Lewis shows how God is with us and guiding us even when we are far from home. But let’s not spend any more time here. It’s time to start the journey to Narnia and the North!

Next time: Chapter 1, “How Shasta Set Out on His Travels”

Further up and further in

Resources used:

Books by C.S. Lewis

The Silver Chair — C.S. Lewis

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe — C.S. Lewis

Prince Caspian — C.S. Lewis

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader — C.S. Lewis

The Horse and His Boy — C.S. Lewis

The Magician’s Nephew — C.S. Lewis

The Last Battle — C.S. Lewis

The Problem of Pain — C.S. Lewis

Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life — C.S. Lewis

On Stories and Other Essays on Literature — C.S. Lewis

Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories — C.S. Lewis

The Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis, Volume 1: Family Letters, 1905-1931 — Editor: Walter Hooper

The Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis, Volume 2: Books, Broadcasts, and the War, 1931-1949 — Editor: Walter Hooper

The Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis, Volume 3: Narnia, Cambridge, and Joy, 1950-1963 — Editor: Walter Hooper

Books about C.S. Lewis

C.S. Lewis: The Companion and Guide — Walter Hooper

Past Watchful Dragons: The Origin, Interpretation, and Appreciation of the Chronicles of Narnia — Walter Hooper

Companion to Narnia: A Complete Guide to the Magical World of C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia — Paul Ford

Into the Wardrobe: C.S. Lewis and the Narnia Chronicles — David C. Downing

Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C.S. Lewis — Michael Ward

The Narnia Code: C.S. Lewis and the Secret of the Seven Heavens — Michael Ward

The C.S. Lewis Readers’ Encyclopedia — Editors: Jeffrey Schultz, John G. West, Jr.

Becoming C.S. Lewis: A Biography of Young Jack Lewis — Harry Lee Poe

The Making of C.S. Lewis: From Atheist to Apologist (1918-1945) — Harry Lee Poe

The Completion of C.S. Lewis: From War to Joy (1945-1963) — Harry Lee Poe

C.S. Lewis: A Life — Alister McGrath

Works by others

A Thousand and One Nights — Translator: Sir Richard Francis Burton

Grimm’s Fairy Tales — Brothers Grimm

The Comedy of Errors — Shakespeare

Twelfth Night — Shakespeare

The Prince and the Pauper — Mark Twain

The Iliad — Homer

The Odyssey — Homer

The Lord of the Rings — J.R.R. Tolkien

Podcasts:

Wade Center Podcast “Into Narnia, Vol. 5, The Horse and His Boy” — Marion E. Wade Center, Wheaton College

The C.S. Lewis Podcast with Alister McGrath “#25 The Horse and His Boy” — Premiere Insights

Pints With Jack “The Horse and His Boy (Part I)”

Theology of Narnia “Episode 009: The Horse and His Boy, Part 1”

The Chronicles of Podcast “Chapter 1, ‘How Shasta Set Out,’ The Horse and His Boy”

Back to Narnia “Chapter 1 - ‘How Shasta Set Out on his Travels’”

Previous articles in the C.S. Lewis read-along

If you’d like to catch up on previous read-alongs, you can see the full collection of articles from the first four Narnia books. I’ve unlocked each of these conclusion posts for everyone, but only paid subscribers will have full access to all the chapter-specific articles.

If you’re wondering why The Horse and His Boy is numbered “Book 3” by the publishers, but we’re reading it fifth, read these explanations for the correct reading order.

The bulk of the story actually takes place during the events of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

Another publisher bought the company, and Bles retired in 1953. The last two Narnia books were published with Bodley Head.

Yet another reason why I disagree with the chronological ordering system. It would require you to put down The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe in the last chapter, read The Horse and His Boy, and then finish Wardrobe.

Were he writing today, Lewis may be more careful in his cultural depictions, but rightly understood this book does not qualify him as bigoted or xenophobic. Being a Christian, he would disagree with Islam as a religion and the way it has influenced culture, but he had no animosity toward Arab people.

Looking forward to getting into the story! It is among my favorites of C.S. Lewis' books!

The Horse and His Boy is my FAVORITE Narnia book! I can't wait for this series to start next week!