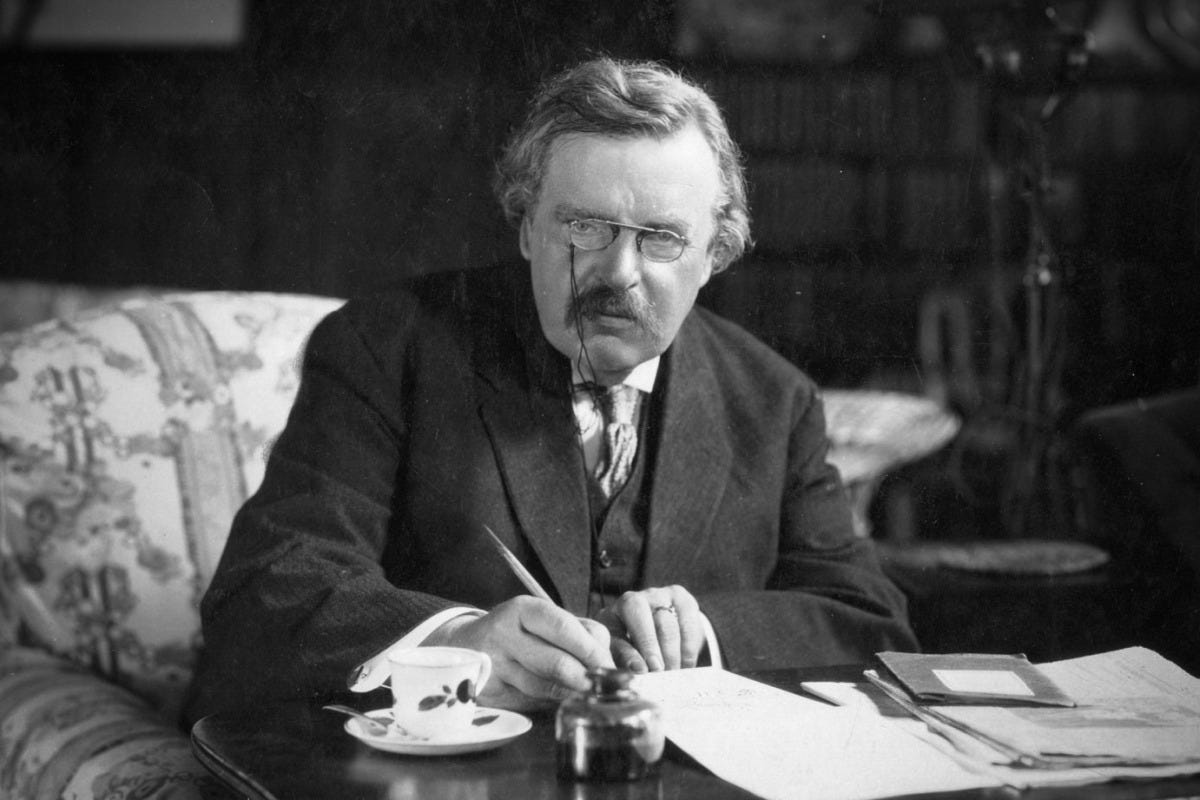

The Apologist Who Shaped C.S. Lewis

The divine trap of G.K. Chesterton

Our next C.S. Lewis read-along, The Magician’s Nephew, will start soon. Prepare for Narnia’s return to the big screen by going chapter-by-chapter through the Narnia prequel.

Become a paid subscriber to gain access to those discussions, previous Lewis read-alongs, and all the archives here. For the next month, you can join for 20% off an annual subscription.

Most know C.S. Lewis as one of the premier Christian apologists who shaped the 20th century and continues to shape Christian thinking today. Many, however, are less aware of the apologist who shaped Lewis—G.K. Chesterton.

After Chesterton died in 1936, Ronald Knox said, “All of this generation has grown up under Chesterton’s influence so completely that we do not even know when we are thinking Chesterton.” Unfortunately, that is likely still the case today.

Additionally, too many remain ignorant of the role Chesterton’s writings played in Lewis becoming a Christian and his subsequent development as an apologist and novelist.

Lewis directly credits Chesterton as a primary influence on his most popular apologetic work. He told Sheldon Vanauken that he was trying to do something similar to Chesterton in his broadcast talks that later became Mere Christianity.

In a later correspondence with Vanauken, he spells out which of Chesterton’s apologetic work he finds so impressive.

Have you ever tried Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man? The best popular apologetic I know.

He says something similar to Rhonda Bodle, telling her that “the best popular defense of the full Christian position I know is G. K. Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man.” Lewis would also place the book in a list of 10 books that “most shaped his vocational attitude and philosophy of life.”

In his spiritual autobiography, Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life, Lewis notes that Chesterton was subtly influencing him toward Christianity, while Lewis remained oblivious.

In reading Chesterton, as in reading [George] MacDonald, I did not know what I was letting myself in for. A young man who wishes to remain a sound atheist cannot be too careful of his reading. There are traps everywhere — “Bibles laid open, millions of surprises,” as Herbert says, “fine nets and stratagems.” God is, if I may say it, very unscrupulous.

Lewis said that MacDonald baptized his imagination, while Chesterton did the same for his intellect; both paved the way for Lewis to later respond to Christ.

Before Lewis knew what was happening, it was too late. He had already been challenged and changed by the wit of Chesterton. Again, he wrote of Chesterton in his Surprised by Joy.

It was here that I first read a volume of Chesterton’s essays. I had never heard of him and had no idea of what he stood for; nor can I quite understand why he made such an immediate conquest of me. It might have been expected that my pessimism, my atheism, and my hatred of sentiment would have made him to me the least congenial of all authors. It would almost seem that Providence, or some “second cause” of a very obscure kind, quite over-rules our previous tastes when It decides to bring two minds together. Liking an author may be as involuntary and improbable as falling in love. I was by now a sufficiently experienced reader to distinguish liking from agreement. I did not need to accept what Chesterton said in order to enjoy it.

His humour was of the kind I like best – not “jokes” imbedded in the page like currants in a cake, still less (what I cannot endure), a general tone of flippancy and jocularity, but the humour which is not in any way separable from the argument but is rather (as Aristotle would say) the “bloom” on dialectic itself. The sword glitters not because the swordsman set out to make it glitter but because he is fighting for his life and therefore moving it very quickly. For the critics who think Chesterton frivolous or “paradoxical,” I have to work hard to feel even pity; sympathy is out of the question. Moreover, strange as it may seem, I liked him for his goodness.

Lewis was entranced by Chesterton’s skill as a writer and rhetorician, but he was also intrigued by Chesterton’s goodness. Many, myself included, have the same sentiments toward Lewis, but we owe much of that to the influence of Chesterton.

If you’d like an introduction to Chesterton and his writing, I’d suggest Trevin Wax’s annotated and guided reading version of Chesterton’s Orthodoxy.

More from The Wardrobe Door

Archive

Recent

Elsewhere

12 Ministry Trends for 2026 — Lifeway Research

Americans’ Trust in Pastors Hits Historic Low — Lifeway Research

Thanks for this. I'll use Lewis' words with the many evangelicals I know who would categorically refuse to read Chesterton, or Aquinas, or Augustine... they're Catholic. They have theological cooties.

I dearly wish American Protestants could get over this. The Catholic (and Orthodox) churches have 2000 years of theology we could learn from, if we could just pull our heads out of our fundamentalism long enough to listen.

That line about humor being the bloom on dialectic rather than flippancy is such a precise diagnostic of what seperates effective apologetics from the stuff that just preaches to the choir. When I first read Cheserton in undergrad, the thing that struck me was how he'd make an argument so compelling that even disagreeing with him felt intellectualy engaging rather than combative.